Cookbook: Difference between revisions

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

Reading XML in octave can be achieved using the java library [http://xerces.apache.org/ Xerces] (from apache). | Reading XML in octave can be achieved using the java library [http://xerces.apache.org/ Xerces] (from apache). | ||

It seems that the matlab's xmlread is just a thin wrapper around the Xerces library | It seems that the matlab's xmlread is just a thin wrapper around the Xerces library. One should note however, that Java functions have the working directory set to the working directory when octave starts and the working directory is not modified by a cd in octave. Matlab has the same behavior, as Java does not provide a way to change the current working directory (http://bugs.java.com/bugdatabase/view_bug.do?bug_id=4045688). To avoid any issues, it is thus better to use the absolute path to the XML file. | ||

You need the jar | You need the jar files xercesImpl.jar and xml-apis.jar from e.g. https://www.apache.org/dist/xerces/j/Xerces-J-bin.2.11.0.tar.gz (check for the latest version). | ||

Use javaaddpath to include these files: | Use javaaddpath to include these files: | ||

{{Code| | {{Code|Define java path|<syntaxhighlight lang="octave" style="font-size:1.1em"> | ||

javaaddpath('/path/to/xerces-2_11_0/xercesImpl.jar'); | javaaddpath('/path/to/xerces-2_11_0/xercesImpl.jar'); | ||

javaaddpath('/path/to/xerces-2_11_0/xml-apis.jar'); | javaaddpath('/path/to/xerces-2_11_0/xml-apis.jar'); | ||

| Line 135: | Line 135: | ||

A sample script: | A sample script: | ||

{{Code|Load | {{Code|Load XML file|<syntaxhighlight lang="octave" style="font-size:1.1em"> | ||

filename = 'sample.xml'; | filename = 'sample.xml'; | ||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

The file <tt>sample.xml</tt>: | The file <tt>sample.xml</tt>: | ||

{{Code|Sample XML file|<syntaxhighlight lang="xml" style="font-size:1.1em"> | |||

<root> | <root> | ||

<data att="1">hello</data> | <data att="1">hello</data> | ||

</root> | </root> | ||

</syntaxhighlight>}} | |||

===Using variable strings in commands=== | ===Using variable strings in commands=== | ||

Revision as of 20:34, 12 March 2014

An Octave cookbook. Each entry should go in a separate section and have the following subsection: problem, solution, discussion and maybe a see also.

Structures

Retrieve a field value from all entries in a struct array

Problem

You have a struct array with multiple fields, and you want to acess the value from a specific field from all elements. For example, you want to return the age from all patients in the following case:

samples = struct ("patient", {"Bob", "Kevin", "Bob" , "Andrew"},

"age", { 45 , 52 , 45 , 23 },

"protein", {"H2B", "CDK2" , "CDK2", "Tip60" },

"tube" , { 3 , 5 , 2 , 18 }

);

Solution

Indexing the struct returns a comma separated list so use them to create a matrix.

[samples(:).age]

This however does not keep the original structure of the data, instead returning all values in a single column. To fix this, use reshape().

reshape ([samples(:).age], size (samples))

Discussion

Returning all values in a comma separated lists allows you to make anything out of them. If numbers are expected, create a matrix by enclosing them in square brackets. But if strings are to be expected, a cell array can also be easily generated with curly brackets

{samples(:).patient}

You are also not limited to return all elements, you may use logical indexing from other fields to get values from the others:

[samples([samples(:).age] > 34).tube] ## return tube numbers from all samples from patients older than 34

[samples(strcmp({samples(:).protein}, "CDK2")).tube] ## return all tube numbers for protein CDK2

Input/output

Display matched elements from different arrays

Problem

You have two, or more, arrays with paired elements and want to print out a string about them. For example:

keys = {"human", "mouse", "chicken"};

values = [ 64 72 70 ];

and you want to display:

Calculated human genome GC content is 64% Calculated mouse genome GC content is 72% Calculated chicken genome GC content is 70%

Solution

Make a two rows cell array, with each paired data in a column and supply a cs-list to printf

values = num2cell (values);

new = {keys{:}; values{:}};

printf ("Calculated %s genome GC content is %i%%\n", new{:})

or in a single line:

printf ("Calculated %s genome GC content is %i%%\n", {keys{:}; num2cell(values){:}}{:})

Discussion

printf and family do not accept cell arrays as values. However, they keep repeating the template given as long as it has enough arguments to keep going. As such, the trick is on supplying a cs-list of elements which can be done by using a cell array and index it with {}.

Since values are stored in column-major order, paired values need to be on the same column. A new row of data can then be added later with new(end+1,:) = {"Andrew", "Bob", "Kevin"}. Note that normal brackets are now being used for indexing.

Swap values

If you want to exchange the value between two variables without creating a dummy one, you can simply do:

| Code: Swap values without dummy variable |

[b,a] = deal (a,b);

|

Collect all output arguments of a function

If you have a function that returns several values, e.g.

function [a b c]= myfunc ()

[a,b,c] = deal (1,2,3);

endfunction

|

and you want to collect them all into a single cell (similarly to Python's zip() function) you can do:

| Code: Collect multiple output arguments |

outargs = nthargout (1:3, @myfunc)

|

Create a text table with fprintf

(a.k.a. A funny formatting trick with fprintf found by chance)

Imagine that you want to create a text table with fprintf with 2 columns of 15 characters width and both right justified. How to do this thing?

That's easy:

If the variable Text is a cell array of strings (of length <15) with two columns and a certain number of rows, simply type for the kth row of Text

fprintf('%15.15s | %15.15s\n', Text{k,1}, Text{k,2});

|

The syntax '%<n>.<m>s' allocates '<n>' places to write chars and display the '<m>' first characters of the string to display.

Example:

| Code: Example create a text table with fprintf |

octave:1> Text={'Hello','World'};

octave:2> fprintf('%15.15s | %15.15s\n', Text{1,1}, Text{1,2})

Hello | World

|

Load comma separated values (*.csv) files

| Code: Load comma separated values files |

A=textread("file.csv", "%d", "delimiter", ",");

B=textread("file.csv", "%s", "delimiter", ",");

inds = isnan(A);

B(!inds) = num2cell(A(!inds))

|

This gets you a 1 column cell array. You can reshape it to the original size by using the reshape function

The next version of octave (3.6) implements the CollectOutput switch as seen in example 8 here: http://www.mathworks.com/help/techdoc/ref/textscan.html

Another option is to use the function csvread, however this function can't handle non-numerical data.

Load XML files

Reading XML in octave can be achieved using the java library Xerces (from apache).

It seems that the matlab's xmlread is just a thin wrapper around the Xerces library. One should note however, that Java functions have the working directory set to the working directory when octave starts and the working directory is not modified by a cd in octave. Matlab has the same behavior, as Java does not provide a way to change the current working directory (http://bugs.java.com/bugdatabase/view_bug.do?bug_id=4045688). To avoid any issues, it is thus better to use the absolute path to the XML file.

You need the jar files xercesImpl.jar and xml-apis.jar from e.g. https://www.apache.org/dist/xerces/j/Xerces-J-bin.2.11.0.tar.gz (check for the latest version). Use javaaddpath to include these files:

| Code: Define java path |

javaaddpath('/path/to/xerces-2_11_0/xercesImpl.jar');

javaaddpath('/path/to/xerces-2_11_0/xml-apis.jar');

|

A sample script:

| Code: Load XML file |

filename = 'sample.xml';

% These 3 lines are equivalent to xDoc = xmlread(filename) in matlab

parser = javaObject('org.apache.xerces.parsers.DOMParser');

parser.parse(filename);

xDoc = parser.getDocument;

% get first data element

elem = xDoc.getElementsByTagName('data').item(0);

% get text from child

data = elem.getFirstChild.getTextContent

% get attribute named att

att = elem.getAttribute('att')

|

The file sample.xml:

| Code: Sample XML file |

<root>

<data att="1">hello</data>

</root>

|

Using variable strings in commands

For example, to plot data using a string variable as a legend:

Option 1 (simplest):

| Code: Using variable strings in commands. op1 |

legend = "-1;My data;";

plot(x, y, legend);

|

Option 2 (to insert variables):

| Code: Using variable strings in commands. op2 |

plot(x, y, sprintf("-1;%s;", dataName));

|

Option 3 (not as neat):

| Code: Using variable strings in commands. op3 |

legend = 'my legend';

plot_command = ['plot(x,y,\';',legend,';\')'];

eval(plot_command);

|

These same tricks are useful for reading and writing data files with unique names, etc.

Combinatorics

Combinations with string characters

Problem

You want to get all combinations of different letters but nchoosek only accepts numeric input.

Solution

Convert your string to numbers and then back to characters.

char (nchoosek (uint8 (string), n)

|

Discussion

A string in Octave is just a character matrix and can easily be converted to numeric form back and forth. Each character has an associated number (the asci function of the miscellaneous package displays a nicely formatted conversion table).

Permutations with repetition

Problem

You want to generate all possible permutations of a vector with repetition.

Solution

Use ndgrid

[x y z] = ndgrid ([1 2 3 4 5]);

[x(:) y(:) z(:)]

|

Discussion

It is possible to expand the code above and make it work for any length of permutations.

cart = nthargout ([1:n], @ndgrid, vector);

combs = cell2mat (cellfun (@(c) c(:), cart, "UniformOutput", false));

|

Mathematics

Test if a number is a integer

There are several methods to do this. The simplest method is probably fix (x) == x

Find if a number is even/odd

Problem

You have a number, or an array or matrix of them, and want to know if any of them is an odd or even number, i.e., their parity.

Solution

Check the remainder of a division by two. If the remainder is zero, the number is odd.

mod (value, 2) ## 1 if odd, zero if even

Since mod() acceps a matrix, the following can be done:

any (mod (values, 2)) ## true if at least one number in values is even all (mod (values, 2)) ## true if all numbers in values are odd any (!logical (mod (values, 2))) ## true if at least one number in values is even all (!logical (mod (values, 2))) ## true if all numbers in values are even

Discussion

Since we are checking for the remainder of a division, the first choice would be to use rem(). However, in the case of negative numbers mod() will still return a positive number making it easier for comparisons. Another alternative is to use bitand (X, 1) or bitget (X, 1) but those are a bit slower.

Note that this solution applies to integers only. Non-integers such as 1/2 or 4.201 are neither even nor odd. If the source of the numbers are unknown, such as user input, some sort of checking should be applied for NaN, Inf, or non-integer values.

See also

Find if a number is an integer.

Parametrized Functions

Problem

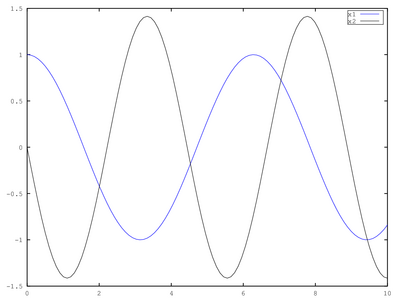

One sometimes needs to define a family of functions depending on a set of parameters, e.g., where denote a the variables on which the function operates and are the parameters used to chose one specific element of the family of functions.

For example, let's say we need to compute the time evolution of the elongation of a spring for different values of the spring constant

Solution

We could solve the problem with the following code:

| Code: Solve spring equation for different values of the spring constant |

t = linspace (0, 10, 100);

function sprime = spring (s, t, k)

x = s(1);

v = s(2);

sprime(1) = v;

sprime(2) = -k * x;

endfunction

k = 1;

x1 = lsode (@(x, t) spring (x, t, k), [1;0], t)(:, 1);

k = 2;

x2 = lsode (@(x, t) spring (x, t, k), [1;0], t)(:, 2);

plot (t, x1, t, x2)

legend ('x1', 'x2')

|

Discussion

In the above example, the function "sprime" represents a family of functions of the variables parametrized by the parameter .

@(x, t) sprime (x, t, k)

|

is a function of only where the parameter is 'frozen' to the value it has at the moment in the current scope.

Distance between points

Problem

Given a set of points in space we want to calculate the distance between all of them. Each point is described by its components . Asusme that the points are saved in a matrix P with N rows (one for each point) and D columns, one for each component.

Solution

One way of proceeding is to use the broadcast properties of operators in GNU Octave. The square distance between the points can be calculated with the code

| Code: Calculate square distance between points |

[N, dim] = size (P);

Dsq = zeros (N);

for i = 1:dim

Dsq += (P(:,i) - P(:,i)').^2;

endfor

|

This matrix is symmetric with zero diagonal.

Similarly the vectors pointing from one point to the another is

| Code: Calculate radius vector between points |

R = zeros (N,N,dim);

for i = 1:dim

R(:,:,i) = P(:,i) - P(:,i)';

endfor

|

The relation between Dsq and R is

Dsq = sumsq (R,3);

|

Discussion

The calculation can be implemented using functions like cellfun and avoid the loop over components of the points. However in most cases we will have more points than components and the improvement, if any, will be minimal.

Another observation is that the matrix Dsq is symmetric and we could store only the lower or upper triangular part. To use this optimization in a practical way check the help of the functions vech and unvech (this one is in the Forge package general). Two functions that haven't seen the light yet are sub2ind_tril and ind2sub_tril (currently private functions in the Forge package mechanics) that are useful to index the elements of a vector constructed with the function vech. Each page (the third index) of the multidimensional array R is an anti-symmetric matrix and we could also save some memory by keeping only one of the triangular submatrices.

Check the Geometry package for many more distance functions (points, lines, polygons, etc.).

Plotting

Get screen size

To get the size of your screen. Do

get (0, "screensize")

|